Nice work!

fix ur spelling

Overall, looks pretty good🙂

This makes no sense!?

These are some examples of peer feedback I’ve seen and heard in my ELA classroom. They include a mixture of broad praise, editing suggestions, vague affirmations, and the occasional empty criticism.

I’d like to say this only happened in my early years of teaching and that I haven’t heard anything like it in years, but that wouldn’t be completely true. I continue to see this kind of feedback occasionally — particularly at the start of the school year or at the beginning of a new unit. But happily, it’s less common now, and most of the peer feedback I hear and read has more depth and detail.

Early on, when almost all of the peer feedback was vague and superficial, it was extremely frustrating. I wanted my students to engage in meaningful dialogue about their learning—to share ideas about what their partner was doing well and what could be improved. I could even envision what the process looked and sounded like. In my mind’s eye, students were demonstrating their learning out loud.

In reality, it looked and sounded little like learning. And it wasn’t even close to what I had envisioned. In fact, the reality was so stark a contrast that I often gave up on the practice for weeks or even months at a time.

Eventually, I realized what may be obvious to some: I wasn’t adequately preparing my students to succeed in the peer feedback process. In other words, there was a lot that I didn’t do. I didn’t give clear expectations. I didn’t model the process. I didn’t provide the necessary supports. And I didn’t give the necessary feedback.

In short, I didn’t teach the process. I assigned it.

But I always came back to the practice. At first, I kept trying it because of my positive personal experiences as both a student and a writer. I knew firsthand about the power of peer feedback, and I wanted my students to experience it as well. I just hadn’t put in the necessary time and effort to make it work in my classroom.

I didn’t really get serious about the practice until I read the research on the topic, which shows strong potential for positive effects on student learning. After reading about the successes other educators were having with the practice, my thinking changed. Instead of thinking, My students just can’t seem to get it right, I began to think, If these teachers can do it, why can’t I?

In the next section, I summarize some key educational literature on the potential impact of peer feedback when done well, which may help change your thinking about the practice.

The Potential Impact of Peer Feedback

John Hattie, in Visible Learning: The Sequel (2023), analyzed 300 studies and 12 meta-analyses, finding that “feedback from students,” or peer feedback, had an effect size of 0.47. This roughly translates to slightly more than a single year’s learning growth, indicating a better-than-average instructional practice.

Similarly, in a meta-analysis of 54 studies on peer assessment that covered students from elementary school through college and across multiple subject areas, Double, McGrane, and Hopfenbeck (2020) found that peer assessment had a small-to-medium effect on academic performance. These findings were higher than those from teacher assessment and no assessment, and about equal to self-assessment. The authors concluded that peer assessment is an effective formative classroom practice.

In a similarly designed meta-analysis, Huisman et al. (2018) analyzed 24 studies on higher education students’ writing performance, finding that the impact of peer feedback on writing was approximately equal to that of teacher feedback and greater than that of self-assessment. These findings are promising for teachers who bemoan the time requirements of teacher feedback.

Dylan Wiliam (2018) also addresses peer feedback in his book Embedded Formative Assessment, which he categorizes within the larger topic of cooperative learning. Here, he shares four factors that make cooperative learning, and thus peer feedback, particularly effective:

- increased student motivation,

- more social cohesion,

- higher personalization of learning, and

- greater cognitive elaboration.

Wiliam and co-author Siobhán Leahy, in their follow-up book Embedded Formative Assessment: Practical Techniques for K-12 Classrooms (2024), argue that peer feedback can be more impactful than teacher feedback because “students are able to be much tougher on each other than the teacher would feel able to be . . . it suggests that, done appropriately, peer feedback may be more effective than teacher feedback because students are more likely to act on feedback from their peers” (p. 147). Here, too, there are significant implications for classroom feedback and the teacher’s after-school workload.

To summarize, the educational literature shows that peer feedback can be an effective instructional strategy for improving student performance. Thus, there is significant potential to positively impact student learning. The question is, how can teachers unlock this potential in their own classrooms?

Below, I provide an overview of the elements of effective feedback, then show what it can look like in the classroom.

Providing Effective Feedback

Not all feedback is equal. Even in peer feedback, there is variation in practice —as some of my past experiences with the practice demonstrate.

If teachers are to help their students realize the learning gains shown in the research, their implementation of peer feedback must be effective. To help, below are some recommendations from experts John Hattie, Dylan Wiliam, and their colleagues for effective peer feedback in the classroom.

3 Guiding Questions

Hattie (2024) argues that teachers need to understand the major variability in feedback effectiveness. He claims that more isn’t always better, and that we might be better served by helping teachers and students to “listen, receive, interpret, and engage in actional feedback” (p. 320).

It is also important, he posits, to consider how and when feedback is given. He presents the following three-question model to focus feedback, along with some strategies for struggling learners:

- Feed Up: Where am I going?

- Beginning strategies: use success criteria and exemplars, identify misconceptions, create mastery goals

- Feed Back: How am I going?

- Beginning strategies: avoid overemphasis on errors, emphasize immediacy, make it concise, match feedback with success criteria

- Feed Forward: What do I have to do next?

- Beginning strategies: use language from success criteria, make it concise, provide necessary scaffolding, make it timely, connect to goals.

These three questions can help teachers plan an effective and strategic feedback process that includes both teacher-student and student-student feedback.

7 Key Attributes

Dylan and Leahy (2024) remind us that “The only good feedback is that which is productive” (p. 111), but guidelines are helpful for teachers—as long as we keep the end goal in mind (which they also make clear later in their book). With this pragmatism in mind, Grant Wiggins (2012), co-author of the influential book Understanding by Design, provides a helpful list of seven attributes of effective feedback:

- Goal-referenced: Connected to learning goals.

- Tangible and transparent: Linked to a desired product or result.

- Actionable: Next steps are clear, and an opportunity for improvement is provided.

- User-friendly: Clear and understandable for the student.

- Timely: Timing matches a student’s stage of learning.

- Ongoing: Occurs throughout the learning progression.

- Consistent: Aligns with teaching, rubrics, and exemplars.

Putting Theory into Practice

Thus far, I’ve presented some educational research and additional literature that support the potentially positive impact of feedback in general and peer feedback in particular. Additionally, I’ve shared guidelines from John Hattie and Grant Wiggins about attributes and structure of effective feedback.

To finish, I present a view of what the peer feedback process can look like in the classroom—using my classroom as an example.

Overview of a Peer Feedback Process (Within a Learning Progression)

Below are eight steps I apply when using peer feedback within a learning progression. As a note, I don’t use this process for each learning target, but for especially important targets. Also, like the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model (Fisher & Frey, 2008), upon which the process is broadly based, it usually occurs cyclically, rather than linearly. The total time varies from one to two weeks, with additional learning targets included along the way.

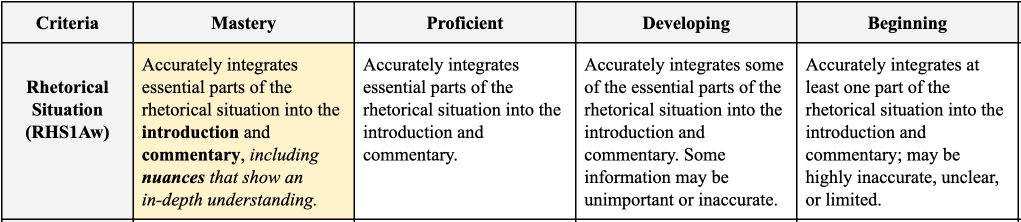

Step 1: Clarify learning targets and success criteria

At the start of a new priority target in a unit, I begin with an overview of the rubric row. I highlight the mastery box because the goal is for all students to achieve that level. It’s just an introduction, but I emphasize some key words that will be important in our work with the target.

I will revisit the rubric often, so my objective this first time is to begin familiarizing students with the target. By the end of the unit, the goal is for them to internalize the expectations so they can self-assess effectively.

Step 2: Direct Instruction

Here, I provide direct instruction on the learning target, which usually includes key knowledge, how to perform the skill, and at least one exemplar demonstrating mastery. Each direct instruction block lasts five to fifteen minutes and typically occurs over multiple class periods.

Step 3: Collaborative Practice

The collaborative practice might be whole class, small groups of three to four, or pairs, depending on the challenge of the target (the larger the group, the more support, and the tougher the target). The key idea is that students have some support as they begin the skill and others to talk to about the process.

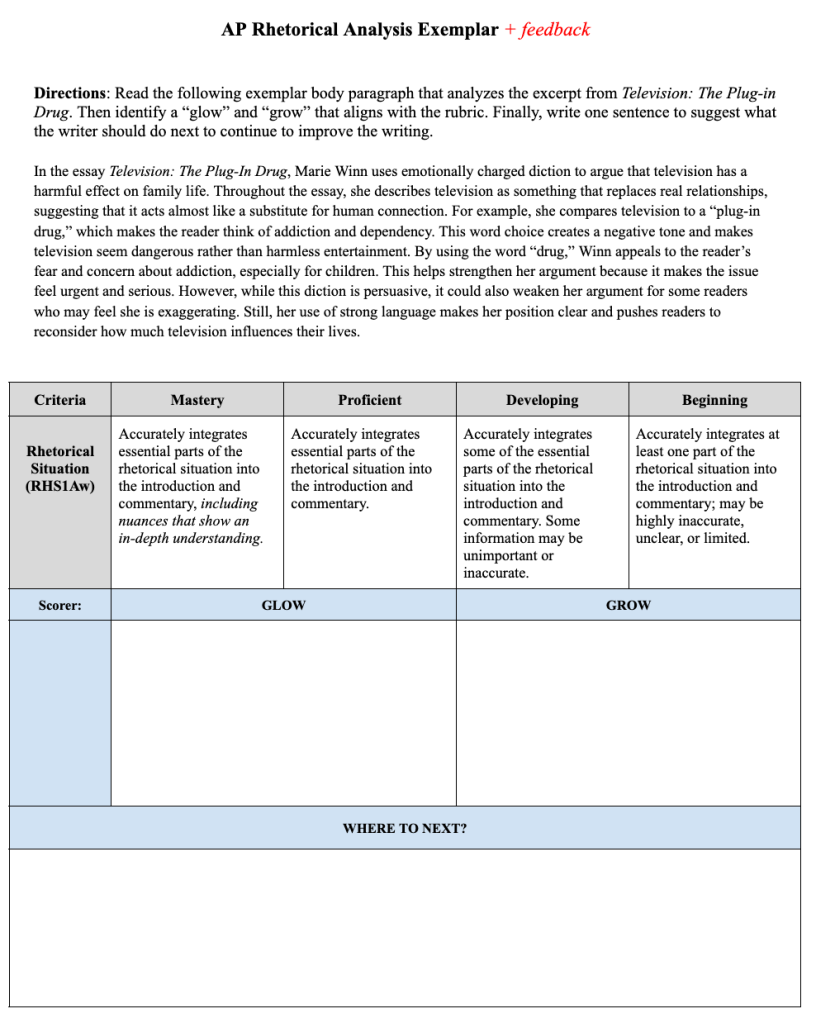

During this time, I make connections between the task, the rubric, and the success criteria. I ask students to periodically share with their partner(s) what’s going well (a “glow”) and what could be improved (a “grow”) in their task. This repeated sharing serves as a primer for later peer feedback and is intended to help them normalize the language of the rubric and success criteria for further internalization.

Step 4: Independent practice

Students perform a task independently to demonstrate their knowledge and/or skills related to the learning target. Earlier in the learning progression, I allow them to use supports if they feel they need them. But later in the unit, they must complete the task without additional supports (unless, of course, they have an IEP that requires particular supports).

Students typically complete multiple independent practices for each target, and the peer feedback usually comes after their second practice.

Step 5: Teacher feedback

I try to provide most of my feedback during class while students are working on independent practice. This way, I can provide them with immediate feedback early in the learning progression that they can apply right away. My goal is to help students understand where they are on the rubric and one step to improve or finish. I also aim to reinforce their growth mindset by reminding them that revision is key to effective writing.

Less frequently, I write feedback on their papers that aims to do something similar to my in-class feedback. However, I find this less impactful, and given the time required for such feedback, I’ve gradually shifted to giving about 75% of my feedback orally and 25% in writing.

Step 6: Synchronous feedback on exemplar

This step typically occurs after they’ve completed collaborative and independent practice and received some feedback from me. This is a collaborative task meant help students achieve a few key goals:

- more precisely understand the success criteria,

- informally self-assess by comparing and contrasting with their independent practice, and

- practice feedback objectively without the emotions that come with providing feedback to a peer.

As shown in the example to the right, I ask students to give a “glow” (something done well), a “grow” (something that can be better), and a next step. During this process, I provide examples of feedback and give oral feedback on students’ written feedback. I also try to share student examples of effective feedback that is specific, detailed, and rubric-aligned.

Step 7: Peer feedback

By this point, students have completed collaborative practices, at least two independent practices, received feedback from me, and practiced providing feedback. Thus, they should be ready to give peer feedback.

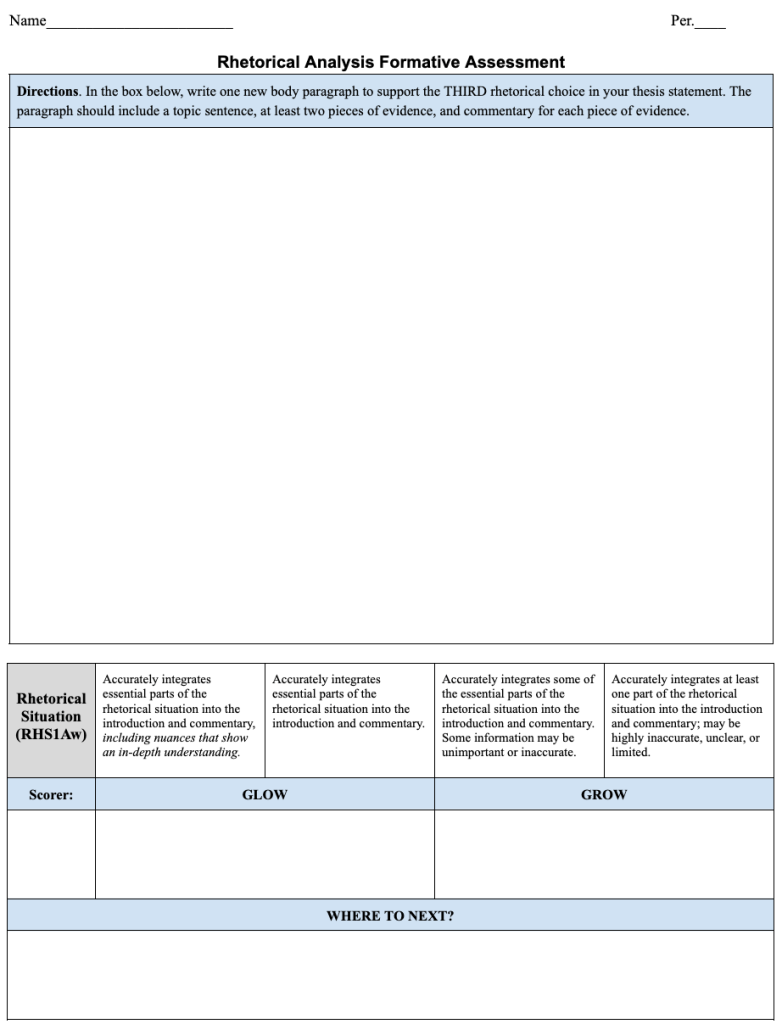

To do this, I typically assign students in pairs, and they exchange papers. They spend about eight minutes reading the response and providing feedback (a “glow,” “grow,” and next step). After, they spend three to four minutes sharing the feedback and asking questions. During this process, I listen and observe, occasionally giving feedback on the process. See the example task to the right. (I plan to give a more detailed description of this step in a future post.)

Ultimately, the peer feedback serves two main purposes:

- To provide the writer with actionable feedback to propel their learning.

- To provide me with formative information about the extent to which the student providing the feedback understands the success criteria and can identify them in writing.

Step 8: Use the feedback

We conclude the process with class time for students to apply the feedback to their writing, keeping in mind Wiliam and Leahy’s (2024) guidance: “The only good feedback is that which is productive” (p. 111).

References

Double, K. S., McGrane, J. A. & Hopfenbeck, T. N. The impact of peer assessment on academic performance: A meta-analysis of control group studies. Educational Psychology Review 32, 481–509 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09510-3

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2008). Better learning through structured teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

Hattie, J. (2023). Visible learning: The sequel: A synthesis of over 2,100 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Huisman, B., Saab, N., van den Broek, P., & van Driel, J. (2019). The impact of formative peer feedback on higher education students’ academic writing: a Meta-Analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(6), 863–880. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1545896

Wiggins, G. (2012, September 1). Seven keys to effective feedback. Educational Leadership, 70(1). ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/seven-keys-to-effective-feedback

Wiliam, D. (2018). Embedded formative assessment (2nd ed.). Solution Tree Press.

Wiliam, D., & Leahy, S. (2024). Embedded formative assessment: Practical techniques for K–12 classrooms. Solution Tree Press.