If you’re working to create more meaningful and accurate grades, one change to consider is no longer grading student practice.

By practice, I mean the classwork and homework that teachers assign to help students develop knowledge and skills. And by no longer grading it, or “ungrading,” I mean completely removing it as a factor in report card grades.

Numerous grading experts emphasize the importance of eliminating practice grades in books devoted to grading reform, including Susan Brookhart (Grading, 2004), Thomas Guskey (On Your Mark, 2015), Joe Feldman (Grading for Equity, 2019), Matt Townsley (Making Grades Matter, 2020), Ken O’Connor (How to Grade for Learning, 2018), and Tom Schimmer (Grading from the Inside Out, 2015).

Practice, of course, matters. It is essential for students to develop important knowledge and skills needed in a class. And in many ways, practice is the key driver of student learning. Traditionally, students are incentivized to complete the practice by earning points, which are recorded in the grade book and on report cards. So, in traditional grading, grades serve as motivators for students to complete the practice and (hopefully) learn.

But this traditional use of grades, and this particular type of motivation, has several problems.

Here are three reasons to stop grading students’ practice:

1. It decreases the accuracy of grades.

Grading classwork and homework can decrease the accuracy of student report card grades IF the primary goal of those grades is to communicate students’ summative achievement levels on prioritized standards.

Here’s why:

Summative assessment is the best tool teachers have to evaluate student achievement. These assessments occur at the end of a learning progression — once the learning process is complete. But practice is inherently formative— it occurs during the learning process. So, including formative grades in a summative report card grade changes the meaning of the grade, resulting in decreased accuracy.

To use a sports analogy, including practice in a report card grade is like judging a football team’s quality by its practice during the week. Sure, you can get a good idea of the team’s potential by how they practice, but ultimately, practice is a means to an end. It’s their performance on game day that matters most and what ultimately counts.

Thus, grades are most accurate when only summative evidence of student achievement is used to determine final grades, which means leaving formative evidence, including homework and practice, out.

2. It discourages a growth mindset.

When teachers grade homework and classwork, they send the implicit message that mistakes aren’t acceptable during practice. Because if they were acceptable, why would students lose points for making them? So grading practice disincentivizes risk-taking, which is crucial to growth and learning. And if students only complete practice that they are confident on, there is little opportunity for growth.

But a growth mindset, defined by author Carol Dweck as the belief that one’s own ability can be increased through effort and learning, depends upon mistakes. In fact, she explains in her influential book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success that mistakes present learning opportunities and, with the right guidance, offer chances for brain growth and resilience.

So when teachers penalize mistakes in practice by lowering grades, they reinforce a fixed mindset, which Dweck describes as the belief that intelligence is innate and that practice and effort have little impact on learning.

3. It encourages point collecting and cheating.

By “point collecting,” I’m referring to the behavior some students display when completing assignments like they are playing a video game. In such cases, the goal is to accumulate points and to “level up,” or in this case, to achieve a specific grade. What’s often lost is any focus on learning. As a result, students’ questions often focus on what they need to do to earn a particular grade and, if the grade is lower than their goal, the minimum they need do to raise it.

Teachers often become frustrated and even exhausted by these point collectors. When students continually ask to submit additional worksheets, activities, or extra credit without regard for the learning, it can feel contradictory to a teacher’s hard work and passion for teaching. In the midst of this frustration, it is easy to forget that it’s the grading of practice that has encouraged this behavior in the first place.

Finally, when students’ main aim is to complete homework correctly without concern about learning, the incentive to cheat increases dramatically. After all, cheating requires less time and effort, and depending on who or what the student is cheating from, it may also increase their likelihood of success. And AI, of course, has taken cheating to a whole new level.

So the key question is: How do we motivate students to complete classwork and homework without points and grades?

I’ve found that many teachers are persuaded by at least some of the reasons explained above for not grading practice. Some even become completely convinced that the traditional practice needs to be eliminated immediately. But that’s the theory.

The practice can be a different matter altogether. Most teachers I’ve worked with or have spoken with, and myself included, have experienced significant challenges effectively implementing this practice. This is because done right, it’s more than simply removing grades from practice. It’s about changing classroom traditions and expectations on the topic of classwork and homework.

Most urgently, it raises the question How can a teacher stop grading homework and classwork and still get students to complete it? And when it comes closer to implementation time, many related questions and fears may arise in a teacher’s mind, such as:

- What will happen when I stop grading practice?

- Will any student even do it?

- Will they think that it’s not important anymore?

- Will they stop listening to me in class?

- Will they stop taking my class seriously?

- Should I even give practice if I don’t grade it?

And on and on the questions and fears may go. Because when grades are used as the carrot and the stick, teachers, understandably, are unsure and even fearful about what happens without these traditional motivators.

Rethinking Student Motivation

But what if part of the ungrading of practice also involved rethinking student motivation? Because when points are no longer used, something must fill this motivation void.

To begin, consider that kids aren’t born with a yearning to earn points. Rather, they are conditioned to behave this way. Beginning around first grade, their classwork, homework, and assessments are graded, and they also begin receiving report card grades.

Quickly, students learn what’s important and what to prioritize from the emphasis adults, both teachers and parents, place on grades. As students progress through the educational system, the importance of points and grades is normalized and internalized to the point that many students and parents consider grading as a foundational part of the educational system.

But I want to suggest that it doesn’t have to be that way. In fact, if we truly value the academic standards that guide our kids’ day-to-day learning, then there is perhaps a certain moral obligation to remove points and grades from the learning process as much as possible, allowing learning to be the central focus.

For this to happen, we can consider intrinsic and extrinsic motivators that teachers can utilize to help students engage in practice without grades.

Intrinsic Motivation

The American Psychological Association defines intrinsic motivation as “an incentive to engage in a specific activity that derives from pleasure in the activity itself rather than because of any external benefits that might be obtained” (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2018).

To associate learning with pleasure and thus activate intrinsic motivation, the learning must be personalized in some way. Below are three ways to intrinsically motivate students to practice without points.

1. Make Practice Interesting and Relevant

Young kids show a high interest in a wide range of topics about the world around them, which motivates them to learn. As they grow and develop, their interests often narrow, and they become more selective about what they are naturally inclined to learn. So their intrinsic motivation to learn becomes highly dependent upon what they discern as interesting or important. One important lever for teachers seeking to increase students’ intrinsic motivation is being intentional about making homework and classwork interesting and relevant.

Here are some ideas for making practice interesting and relevant for students:

- Make the practice active by getting students moving

- Make the practice social by giving students strategic collaborative tasks

- Connect the practice to students’ lives–whether past, present, or future

- Keep it varied and fresh by frequently changing the practice format and task type

- Share and show your interest in the practice, modeling the motivation you hope to see from students

2. Provide Choice and Voice

Choice and voice are two common ways to increase student intrinsic motivation by increasing student agency. Providing students with choice in the learning process gives them some autonomy, which can create a closer connection between them and the learning process. Autonomy is often associated with greater satisfaction and happiness, all tied to the connection to “pleasure in the activity” we seek. This idea is explained in Edward Deci and Richard Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory (2017), which is worth further investigation for those especially interested in the topic.

In the classroom, consider the following ideas for increasing student choice:

- Allow students to choose one of three reading options

- Provide a “menu” of tasks to practice their learning on priority standards

- Give students a choice of the supporting standard they learn after reaching proficiency on the required priority standards

- Let students choose the problems they will solve from a range of available questions

And to increase student voice, consider some of these ideas:

- Let students choose how they’d like to collaborate on a task (e.g., pairs, small group, Socratic Seminar, etc)

- Ask students to provide feedback at the end of a unit about what helped them to learn, what didn’t help them to learn, and what would be better next time

- Ask students to create a list of discussion questions to guide class discussion in a unit

- Collaborate with students to create guidelines for classwork and homework, including quality, timelines, acknowledgments, and penalties.

3. Guide Self-Assessment and Goal-setting

Self-assessment is a process of reflection and evaluation in which students judge their own achievement against a given set of success criteria or learning expectations. To be successful in this process, students must be able to complete multiple tasks, including

- understanding the success criteria for the target(s) or standard(s),

- objectively comparing their evidence to the criteria, and

- making a judgment about the current state of their achievement, based on the evidence.

Self-assessment is one of my favorite activities to use in the classroom, but it can definitely be challenging. I find the most success when students self-assess near the end of a learning progression or unit — once they’ve had time to internalize the learning expectations. It can also be more effective after they’ve received feedback from their peers and from me. By this time, they’ve been formatively assessed several times, and they’re expected to have a pretty good idea of their current achievement level.

This can motivate students intrinsically by giving them greater ownership of their learning, which again ties into Self-Determination Theory. By tying self-assessment to goal-setting, students can extend this metacognitive process beyond a single self-assessment event to track their learning across one or more learning progressions. Goal-setting could involve reaching a specific achievement level on particular standards or targets, seeing growth in achievement, or even reaching a targeted practice completion rate.

Extrinsic Motivation

The American Psychological Association defines extrinsic motivation as “an external incentive to engage in a specific activity, especially motivation arising from the expectation of punishment or reward” (APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2018). In our context, we’re considering non-grade methods to get students to complete practice because of the expectation of punishment or reward.

1. Record & Communicate Practice

Just because it’s not graded doesn’t mean it can’t be recorded. By recording some (but not all) practice, teachers stay organized in their records of student practice and can track patterns of student learning. They can also communicate student practice completion with parents; however, extra care must be taken to inform parents that it isn’t graded.

Finally, by recording practice, it sends a message to students that it does still matter, even though it’s not graded. I often hear teachers who are surprised that students still worry about missing assignments in the grade book, even when there are no grades. This reiterates the idea that the simple act of measuring and recording practice motivates students to complete the practice.

2. Provide Teacher & Peer Feedback

While feedback can serve as both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, depending on how the student receives it, here it’s presented through the extrinsic lens. In many cases, knowing that someone else will review their work can motivate students to minimize the “punishment” of criticism and maximize the “reward” of praise. I suggest using both teacher and peer feedback to do this.

For teacher feedback, early and often is key. By providing feedback while students are completing practice, teachers can instantly boost student motivation and simultaneously minimize the time they have to spend after school marking up papers with feedback.

As with self-assessment, peer feedback usually occurs later in the learning progression, once students understand the success criteria and have received feedback from the teacher. The teacher’s feedback can also serve as a model for the type of feedback they should give peers. A good strategy to begin the peer feedback process is to guide students in giving feedback on a sample paper. After going through the process together, feedback from a peer can be the natural next step.

But whether it’s teacher or peer feedback, here are several guidelines that effective feedback should follow:

- Make it clearly connect to success criteria or rubrics

- Make it descriptive, not judgmental

- Make it actionable, helping the student know the next steps

- Make it timely, ideally during or immediately after the practice

- Make it focused, typically two or three areas to address

(Hattie & Clarke, 2019)

3. Require Prerequisites

It’s likely that some students (in my experience, a small minority) will try to test the system and complete minimal practice once they learn that homework and classwork will be ungraded. While it’s true that sometimes students need to learn the hard way, we also want to make sure all students have at least a minimum level of learning and preparation before taking a summative assessment. Otherwise, we’re simply setting them up for failure. To do this without grades as motivators, some teachers require that a prerequisite be completed before students can take the summative assessment. With this requirement, students who haven’t completed the prerequisite can’t yet take the summative assessment.

To be clear, the goal here is not to be punitive — it’s to ensure that all students can succeed on an assessment. And without practice or demonstration of knowledge or skills, it’s unlikely that a student will succeed. The trick, though, is to ensure the prerequisites aren’t too burdensome; otherwise, it may prevent too many students from taking the assessment.

Here, an example can be especially helpful to envision what this could look like in your classroom. So, below is the way I use the prerequisite requirement in my 11th grade English classroom.

While my students are expected to complete all practice, the “essential practice” is a requirement before they take the summative assessment. It comes several days before the end of the learning progression, and it includes practice on one or more priority standards that appear on the assessment

In form, it mirrors the summative assessment. That is, the format is the same, but the content of the questions or passages students must read differs. This is key because it helps students know what to expect on the summative assessment and provides additional motivation to complete it. It can be thought of as a practice test or a scrimmage before the game.

And just as important is what students do with it afterwards. While I provide feedback during practice, students must give and receive peer feedback after they finish. Once this process is finished, students submit it, and I record it in the grade book for 0 points as “complete.”

And for the students marked “incomplete”? They must complete the essential practice while other students are taking the summative assessment. Once finished (usually by the end of the testing period), they take a different version during the make-up time I’ve scheduled.

5 Steps to Begin Ungrading Practice

I hope the information presented above is helpful, but I also realize that getting started can be the hardest part. So here are five steps to begin ungrading practice in your classroom.

- Begin by ungrading just one classroom assignment. Inform students that you won’t be grading it, and explain why. Don’t make the common early mistake of keeping the change a secret, which can be seen as deceptive and misguided. Students must be informed for both transparency and motivational reasons.

- Clearly explain the relevance of the standard they are practicing for their success in the unit and in their life.

- Provide some choice and voice in the assignment.

- Provide targeted feedback as students work, and after they finish, guide them through a round of peer feedback.

- Finally, record the assignment in the gradebook for 0 points or no credit (whichever your platform allows), and share classwide feedback about how the class did on the practice. Finish by sharing how the practice leads to the next step in the learning progression.

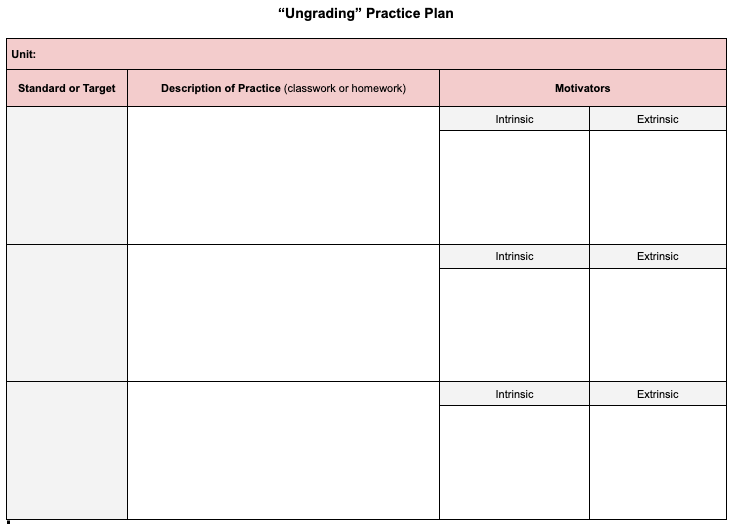

Here is an organizational tool for planning work (Google doc link).

Whether you’re just beginning grading reform or refining your practice after years of experience, using classwork and homework as ungraded practice is crucial to creating accurate, learning-centered grades. Actively considering student motivation when planning and using classwork and homework can help ensure that ungrading is as sound in practice as in theory.

References

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2018). Extrinsic motivation. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/extrinsic-motivation

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (2018). Intrinsic motivation. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/intrinsic-motivation

Brookhart, S. M. (2004). Grading. Pearson Education.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Feldman, J. (2019). Grading for equity: What it is, why it matters, and how it can transform schools and classrooms. Corwin.

Guskey, T. R. (2015). On your mark: Challenging the conventions of grading and reporting. Solution Tree Press.

Hattie, J., & Clarke, S. (2019). Visible learning: Feedback. Routledge.

O’Connor, K. (2017). How to grade for learning: Linking grades to standards (4th ed.). Corwin.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Schimmer, T. (2016). Grading from the inside out: Bringing accuracy to student assessment through a standards-based mindset. Solution Tree Press.

Townsley, M., & Wear, N. L. (2020). Making grades matter: Standards-based grading in a secondary PLC. Solution Tree Press.